Whale shark shipping collisions may increase as the ocean warms

Moving towards a step change in marine animal tracking for conservation

LED BY

The Global Shark Movement Project (GSMP) is a scientific research project bringing together 40 shark research teams spread across more than 100 institutes in 26 countries.

Our aim is to advance scientific knowledge of shark behaviour, ecology, conservation and fisheries science that can be used to inform improved management of threatened sharks and ocean biodiversity. The unique database of shark tracking and environmental data we have assembled by working as a global research community enables new science discoveries that inform policy relating to shark conservation and the sustainable management of shark populations.

GSMP was founded in 2016 and is coordinated from the Marine Biological Association Laboratory in Plymouth,UK.

The Global Shark Movement Project – GSMP – is an international scientific research team focused on tracking the movements and changing habitats of pelagic sharks and quantifying the threats they face in order to inform evidence-based conservation

GSMP brings together scientists and the shark tracking data they collect within a single database to enable novel research in shark behaviour, ecology, conservation and fisheries science.

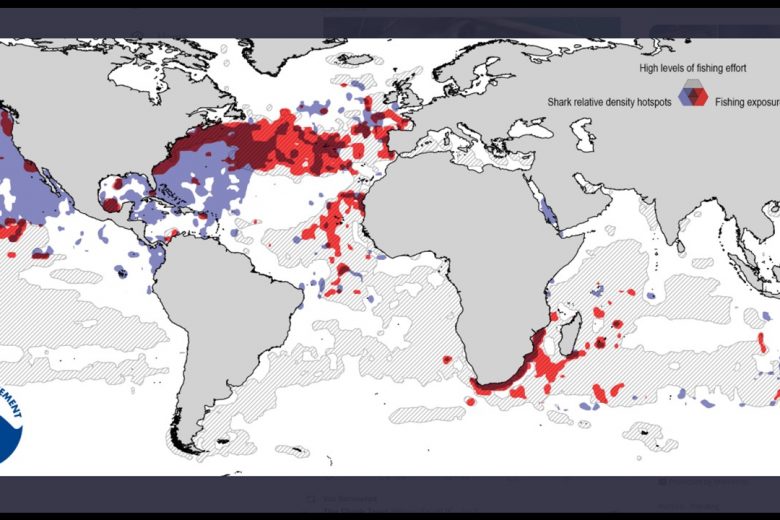

GSMP has tagged sharks right across the North Atlantic and has tracked them over huge distances. More than 150 blue sharks, 130 tiger and 120 shortfin makos have been tracked here since 2002. The fastest swimming shark, the shortfin mako, moves up to 60 km a day. GSMP data have identified shark spatial hotspots and revealed that they are overlapped significantly by longline fishing activity – sharks here are being overfished and have very little management to control catches. However, GSMP analyses can help identify spatially where conservation should be focused. [Read more in Projects and Publications]

GSMP researchers have spent years studying shark movements from U.S. and Canadian waters, including great white sharks. A famous white shark called ‘Lydia’ tagged in U.S. waters headed west and crossed the Mid-Atlantic Ridge before turning round and heading back. Protected in U.S. waters after decades of exploitation, white sharks there appear to be increasing in abundance.

GSMP is tagging threatened sharks throughout Florida waters and the Caribbean Sea. The oceanic whitetip shark is ‘Critically Endangered’ in the western central Atlantic with the population at a fraction of its former biomass. GSMP researchers have tracked its space use, finding that some Caribbean marine reserves banning industrial fishing may protect a significant proportion of habitats.

Blue and shortfin mako sharks are being tracked by GSMP here because these sharks are faced with a double whammy: climate-driven ocean deoxygenation that leads to oxygen minimum zone (OMZ) expansion and shark habitat compression coupled with high fishing intensity above the OMZ. These combined effects of shark habitat compression and high fishing effort likely make pelagic sharks here more susceptible to surface longline fisheries than adjacent waters. Therefore, this may be a region requiring special measures to mitigate climate and fishing effects on sharks. [Read more in Projects]

GSMP scientists are following the movements of whale, tiger and oceanic whitetip sharks in tropical waters off Brazil to find out how changing environments influence movement patterns and spatial distributions. Key questions concern where sharks migrate to and where and when they interact with longline and purse seine fisheries.

GSMP researchers stationed at this remote island have been tagging tiger and Galapagos sharks to find out whether they remain close to oceanic islands for much of the time, or are just passing through on long-distance migrations spanning the South Atlantic. Determining if space use of some pelagic shark species is relatively localised around remote islands may help devise management measures to better protect them in these areas.

GSMP has found few satellite trackings of pelagic sharks have been undertaken in the South Atlantic, which identifies a real knowledge gap. This is of concern because longline fishing effort is high throughout the high seas of the South Atlantic.

White sharks and bull sharks are being tracked by GSMP teams off South Africa to better understand their use of coastal and oceanic waters. White sharks are protected in South African waters so it is important to know where they go in relation to people using the sea, but also to determine whether they are at risk from fisheries capture by occurring in the fishing areas at the same time as fishers.

GSMP scientists have been tagging and tracking blue, tiger, whale, white, silky and bull sharks in the rich, deep waters between southeast Africa and Madagascar. The high productivity at depth may be one reason why whale sharks here have been tracked diving down to over 1 km depth.

Silky, whale and bull sharks are being tracked in the Seychelles. It is thought the impacts of fisheries on Indian Ocean sharks have been as severe as those documented in the Atlantic and Pacific, however knowledge about where Indian Ocean sharks and fisheries interact is largely missing. Despite bull sharks being thought to remain in shallow coastal waters, GSMP researchers have discovered a pregnant bull shark migrated across open ocean from the Seychelles to Madagascar and back, a 4,000 km round trip, highlighting the need for international collaboration to manage the regional population.

White sharks have been tracked migrating up the west coast of Australia, from the southwest tip to Ningaloo Reef in the north during October and November. Shortfin makos have also been tracked here by GSMP scientists, which raises the question whether both species converge there to feed on fishes moving from shelf to oceanic waters seasonally.

Blue, shortfin mako and white sharks are tracked by GSMP researchers off southern Australia. Understanding the movements of blue sharks and shortfin makos is important to inform management, since these species are globally the most commonly caught pelagic shark by longline fisheries. White sharks in this region, as off South Africa and Californian, feed on seals seasonally resident at colonies, so knowing their movements can help to find out if sharks are similarly resident seasonally and where they go to after the seals disperse to sea.

Pelagic shark movements here are influenced by the rich waters of the East Australia Current and those of the Great Barrier Reef. Blue, shortfin mako, tiger and white sharks are being tracked by GSMP. Coastal and shelf movements of tiger sharks are common in this region and the large scale movements they make away from relatively small protected areas (e.g. Australian Commonwealth Marine Reserves and coastal barrier reef marine protected areas) expose them to fisheries. GSMP is studying the spatial dynamics of sharks and fishing vessels.

The warm-bodied porbeagle and white sharks are being studied by GSMP researchers. The porbeagle shark is assessed as globally ‘Endangered’ and is managed by strict quotas in New Zealand waters. It is necessary to understand its movements, preferred habitats and spatial overlap with fisheries because when caught as bycatch on longlines some 40% of individuals are already dead. GSMP tracking studies of sharks and longliners can help identify where most bycatch is occurring, and inform bycatch mitigation to protect the population given the high mortality from discarding.

Whale sharks have been tracked by GSMP teams in this region, but generally very little is known about the movements of other pelagic shark species here. This is a region where GSMP aims to focus more attention.

GSMP scientists have begun to track sharks in this region including Galapagos sharks. However, this region represents a major knowledge gap for pelagic shark movements and behaviour because seemingly few have been tracked here. This region needs to be a focus of collaborative shark science to reveal where sharks go and what they are doing in relation to known environmental changes and anthropogenic impacts already occurring.

The Northeast Pacific is one of the most intensively studied regions with respect to pelagic sharks. Between 2000 and 2010 several hundred pelagic sharks including white, salmon, blue and shortfin makos were tracked as part of the Tracking of Pacific Pelagics (TOPP) project. GSMP is fortunate to be able to link up with this research team to incorporate their freely available data into global analyses.

GSMP researchers working in the Galapagos Islands and other islands in the region already work together very closely within the MigraMar project. Tiger, whale and hammerhead sharks are being tracked to understand their basic ecology in this incredibly productive part of the Pacific ocean, and how their space use overlaps with threats such as longline and purse seine fishing. Illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fisheries are problem in this region so the scientists are also quantifying the spatial protection that can be achieved within marine reserves given the necessary enforcement.

Shortfin mako sharks are being tagged and tracked to determine space use patterns and diving behaviour. Analyses show makos move throughout the region over huge distances, seemingly always on the move. They spend most time diving in mixed layer depth but occasionally dive down to 900 m.

Tens of millions of pelagic sharks are harvested each year by high seas fisheries but with little or no management for the majority of species. Sharks are particularly susceptible to the effects of human exploitation due to slow growth rates, late age at maturity and low fecundity, traits making them comparable to marine mammals in terms of vulnerability. Global data on pelagic shark habitat hotspots, spatial patterns of vulnerability in relation to fisheries, and how sharks respond to changing environment are lacking, precluding understanding where in the global ocean conservation needs to be focused.

GSMP tracks free-ranging sharks using sophisticated, miniature electronic tags that are temporarily attached to them for logging and/or relaying data about their movements, behaviour, physiology and/or environment.

Understanding the complexities of shark movements and distributions with respect to changing environment and anthropogenic threats is crucial for improving conservation.

GSMP promotes the use of its scientific results to inform policy relating to shark conservation and the sustainable management of populations.

GSMP research teams engage actively with regulatory authorities and policy makers to communicate new science that can be used to improve shark conservation.